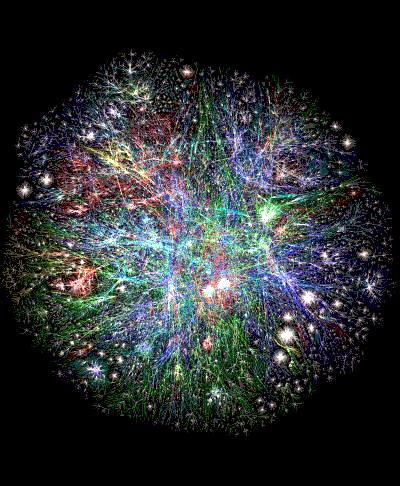

Almost a third of the world’s population is now wired up to the World Wide Web. With over 800m users, Asia is home to the largest Internet-enabled contingent, where 42% of cyberspace resides.

By comparison, North America constitutes a mere 13.5% (266m) of Earth’s online populace, whilst Europe is home to a slightly chunkier 24.4% (475m). The remaining 20% is spread across Africa, the Middle East, Latin America and Oceania/Australia.

If this tells you anything, it tells you this: the Internet knows no boundaries. And the non-English speaking world is catching up – the use of Arabic online increased by over 2500% in the past ten years, while Chinese and Spanish have increased by 12 and 7 times respectively. English didn’t even triple-up.

The point to this is that all the web designers and developers of the world need to think global from the start, whilst they’re constructing their carefully crafted web pages.

Big companies have big budgets to properly localize their websites in each of their international markets. This means they can have in-country domains (.de for Germany, .es for Spain etc) with fully localized and translated content that’s optimized for local search engines. And that’s the ideal scenario.

But not every company has multi-million dollar revenues to splurge on their international online endeavours. So what can the little guys do to ensure their websites are as internationally friendly as possible?

Well, in the first instance, it will actually help to look at some of the tricks the big guys pull. And to help analyse these tricks, I enlisted the help of John Yunker, co-founder ofByte Level Research, a boutique research and consulting company dedicated to the art and science of web globalization.

Yunker is also co-producer of the annual Web Globalization Report Card, and he was author of the first book devoted to the emerging field of web globalization, Beyond Borders: Web Globalization Strategies. He knows his stuff.

Up until 2011, Google pretty much had number one spot reserved on Byte Level’s Web Globalization Report Card. And it will be useful to look at why that’s the case.

A ‘world ready’ design

All good global websites must feel locally relevant. And it’s easier to localize websites that don’t have many images in their designs. Yunker notes that Google in particular has always excelled at building scalable products, and part of this has meant designing minimalist interfaces:

Of course, Google has the financial muscle to professionally localize all its text for each of its forty languages. But by not including imagery – especially of people – in its design, it saves the company a massive localization headache. Facebook employs the exact same tactic too.

This basic rule of thumb can be applied to websites of all size and scope. Keep your interface as image-free as possible, and let text and globally-recognisable icons be your guide. And if you do use images, make sure they’re not country or culture specific.

Speaking in tongues

Design and interface aside, there’s no escaping the role that language plays in the website globalization and localization process. And this is partly why Google has always ranked so highly in Yunker’s Web Globalization Report Card.

“Google really raised the baseline for languages expectations for everyone else. Back when most companies were happy to support 10-20 languages, Google localized its search interface to support 60 languages. The search engine now supports 120+ languages and most Google services support between 40 and 50 languages. Google was quick to realise it had to invest in languages if it was going to succeed in local markets.”

Of course, to employ native writers or translators to cover multiple languages will require a budget, so this probably won’t be your priority if you’re business is just starting out.

Plan to succeed

But you have to plan for success, which means ensuring your website can easily be adapted for other languages in the future. And this is where Unicode comes into play.

Unicode is a computing industry standard, and its aim is to enable the consistent representation of text, irrespective of the script.

For example English, Arabic, Chinese, Hebrew, Thai — any written language, whether it reads left-to-right (LTR) or right-to-left (RTL), is catered for. Unicode has a repertoire of well over a hundred thousand characters, spanning ninety different scripts. UTF-8 is the most common character-encoding for Unicode, and it’s a variable-length encoding that represents every character in the Unicode character set. UTF-8 is becoming the default encoding system for e-mail and websites, and by adopting this you can ensure your website is compatible with almost any language.

Space…the final frontier?

Websites should be as flexible as possible to future adaptation. Some languages require less or more pace than English to convey the same message.

The specifics of how much more/less space one language needs over another is difficult to convey, given that there are 101 ways of saying something in many languages. But as a general rule, Asian languages such as Japanese and Chinese typically require less space on paper than English, whilst many European languages such as French and German tend to consume more space.

For web developers, this means if a website needs to be translated in the future, it’s important to keep the content and design separate. This means avoiding fixed width structures containing text – space should be given to allow for expansion and contraction depending on the length of the translated text. And that’s where using cascading style sheets (CSS) helps – it keeps content and design apart.

Translation: the rise of the machines

Even if you never plan to translate your website, you should at least make it ‘translation friendly’ by giving users the option of using machine-translation engines such as those provided by Google or Bing. Yunker states:

“I’m particularly impressed with how integrated machine translation is within Google Chrome. So I would argue against embedded text within any visual – and Flash is a big problem too in this regard. I’m a huge fan of text-only designs.”

This is a good point. Translation tools such as Google Translate can’t detect text that’s embedded within images or Flash animations, so by adopting a simple, clean, text-only design philosophy, this will help the end-user translate a website for themselves with a click of a button in their browser. It does seem a little crazy to think that Google now supports forty languages, but a user might not be able to use the power of machine translation simply because the text is locked in a graphic. If you’re wondering about the quality of machine translations, Yunker had this to say:

“Google took machine translation mainstream. Before Google, machine translation was largely a joke. And while the quality is still highly uneven, it’s hard to argue that it doesn’t have a role to play. I use it quite frequently.”

The need for speed

Another benefit of a text-only approach, as Yunker points out, is that “you have more flexibility as you repurpose the text for mobile, and for different bandwidth environments.”

We reported earlier in the week how broadband prices have dropped by an average of 50% around the globe, but it remains unaffordable in many developing countries. In 32 of the countries designated by the UN as ‘least developed’, the monthly price of an entry-level fixed broadband subscription equated to more than half of the average monthly income. And in 19 of those countries, a broadband connection costs more than 100% of the monthly GNI per capita, whilst broadband in a handful of developing countries costs more than ten times the average monthly income.

So if you load your website with chunky, bandwidth-sapping Flash animations and graphics, this could preclude millions of people from accessing your website, simply because they don’t have broadband on tap.

The future’s social

Whilst Google has typically always ranked top on Yunker’s Web Globalization Report Card, Facebook muscled its way to pole position in 2011.

Yunker states that Facebook has been particularly innovative over the past year from a multilingual perspective. And he believes that these innovations have big implications for how millions of companies integrate social networks across their local websites.

Facebook’s social plugins, kick-started last year with the launch of its Open Graph API, have been enormously successful. Over two million websites now integrate with Facebook, and 10,000 new sites are joining each day. But as Yunker points out, what many haven’t noticed is that these plugins are also multilingual.

It seems the chief reason why Facebook is a leader on the website globalization front, is because of the direction in which it’s taking the Internet. Yunker notes:

“A multilingual social graph is being developed by the many millions of people clicking ‘Like’ buttons. Privacy issues aside, it’s going to be very interesting to see where Facebook takes this platform as it matures.”

It seems that companies are certainly wising up to the needs of the global community. Yunker points out that the average number of languages supported by global websites is 23 – almost twice the number in 2005. Whilst the companies in question are large corporations such as Apple, Siemens and Honda, it’s still indicative of how the web is truly globalizing.

Near the head of the pack is Google, which operates what Yunker calls a ‘40 x 40’ programme: 40 applications supporting 40 languages.

“In a sense they’ve (Google) selected a baseline to work within. Right now, with 40 languages you get between 95% and 98% of all Internet users, which is more than enough for most companies.”

Facebook, of course, trounces this figure thanks to its crowdsourcing translation programme, which it more or less invented. As Yunker highlights:

“Facebook went from 2 to 74 languages in record time, and it’s clearly a business that all companies must follow closely in the years ahead.”

But there’s also one other small trick web designers and developers can learn from the big guns that are already conquering cybserspace.

What do online brands such as Facebook, Google, Twitter, MySpace, tumblr, LinkedIn, Skype, PayPal and WordPress have in common? Sure, they’re all massively successful digital platforms with a strong social element ..but what else?

Well, as is demonstrated in this infographic, they’re all very blue. You see, colors mean different things in different cultures, but blue is generally regarded as the most ‘trusted’ color around the world, which is partly why it features so highly with the big brands. This doesn’t mean you have to copy Facebook or Twitter’s color scheme, but it does mean you should consider your website’s look and feel very carefully in the design stage.

Tools of the trade

Of course, there’s a multitude of tools at your disposal, ones that can help take your website to the masses without the need for a Google-sized budget.

We’ve already mentioned Google Translate, but we’ve previously written about a neat little crowdsourced translation app called OneSky, which allows website or app owners to tap into a vote-based translation service from the people that use the web or app. It’s not free and instant like Google Translate, but it might just secure you a better quality of translation.

And if you operate an e-commerce website, it’s often the shipping logistics that are the real pain. UPS has a useful app that can be integrated with your website, which helps users estimate the cost of delivery, screen for embargoed countries, check import compliance and a number of other key points.

Or if you run a blog that talks a lot about money, you can install a currency converterwidget to make it easy for those from other countries to convert to their currency.

Internationalizing doesn’t have to mean making wholesale changes to your website, it can simply mean making it easier for those from other countries to engage with your website.

You may well be thinking about local markets in the short-term, but if your business takes off in a big way, your website should appeal to everyone, everywhere. Think global.

Comments